Episode 2: Rendering the empty board and partial function application

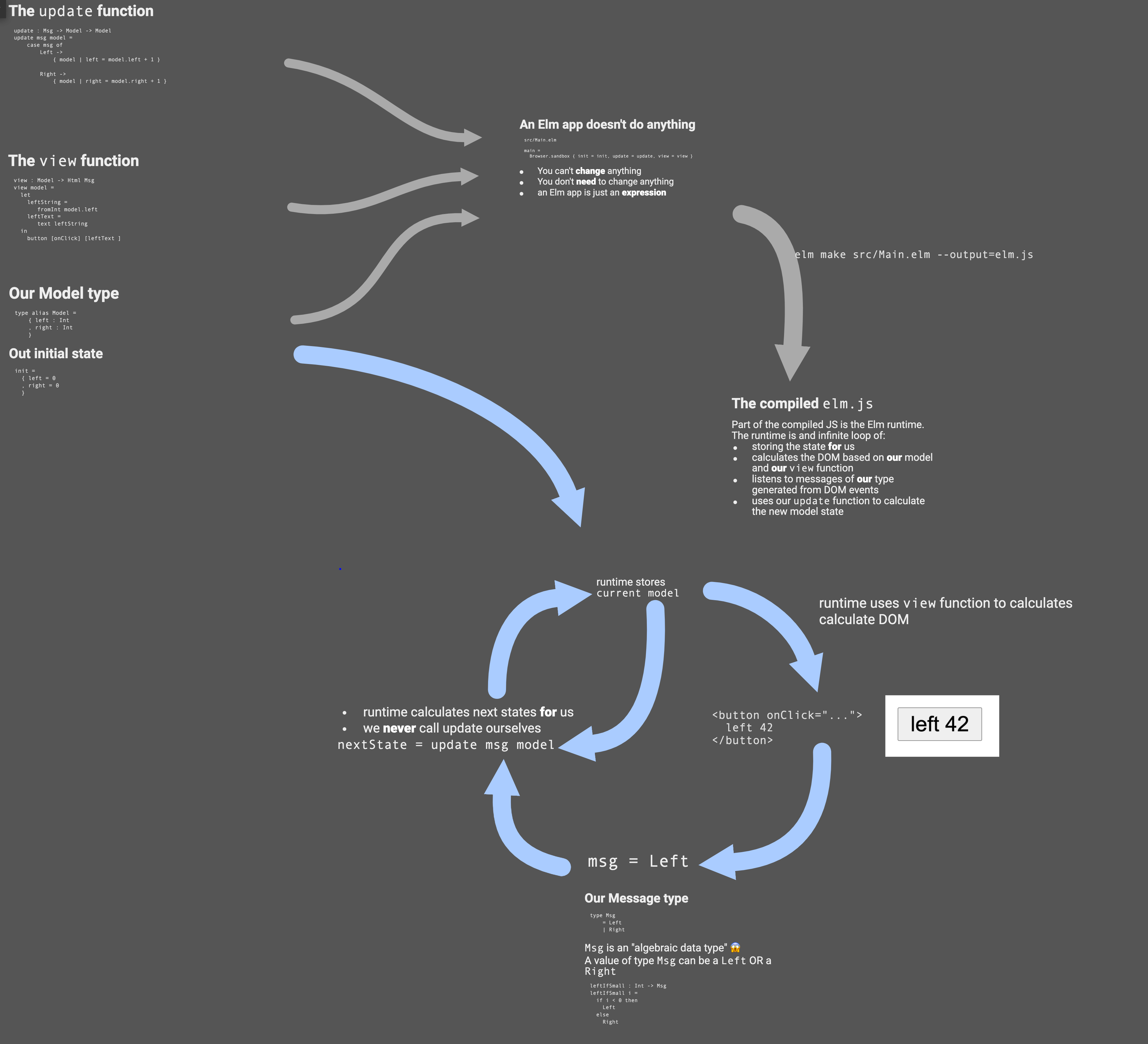

After we looked at the structure of an Elm app line by line last week, we had a more abstract look at the mechanics of an Elm app today. But after that we jumped right into the code that would render the empty Tetris board.

The state of the code at the end of the episode is available on the episode2 branch on Github

The development of an Elm application starts most of the time with thoughts about the central data types. That does not mean we have to know all the types and definitions from the begining though. We start with a very limited model that only contains what’s necessary for our first goal: A board of empty rows. I have high confidence that the strong type system of Elm will support me to quickly develop the data model without introducing regressions.

There was one aspect that we looked at that I’d like to give a bit more context on. The way function are declared in Elm might seem a bit alien to users of more classic programming languages.

fieldView : Int -> Int -> Html Msg

fieldView row column =

rect [x (col * 10), y (row * 10)] []

The first row is the signature of the function and it can be read like this:

fieldViewis a function with two parameters of typeIntand it returns a value of typeHtml Msg.

“But why are the parameter Types not enclosed in parenthesis like in a normal language?”

The reason for that is, that this is not the only way the signature can be interpreted! You could also read it like this:

fieldViewis a function that recieves oneIntparameter. The return value is a (new) function that recieves one (the other) parameter of typeIntand returns anHtml Msg.

Pratically speaking that means fieldView will return either an Html value or a function depending on with how many parameters we call it.

“But what is that good for!?”

Using this principle is called partial application. And it only really shows its strength when we use it in combination with functions that expect other functions as parameter.

The most prominent example from this family of function is map. It applies a given function to each element in a list.

A simplified version of the function that renders the board looks like this:

boardView : Html Msg

boardView =

let

rowNumbers = range 0 20

in

map rowView rowNumbers

rowView : Int -> Html Msg

rowView rowNumber =

let

columnNumbers = range 0 10

in

map fieldView columnNumbers

fieldView : Int -> Int -> Html Msg

fieldView row column =

rect [x (col * 10), y (row * 10)] []

This code will actually not compile, because the return value of rowView doesn’t match with what we’ve declared.

We’re calling map with fieldView. A function that will return another function when we call it with one Int.

But we need to get an Html back!. The solution is to “bake in” the rowNumber into fieldView and create a new function that only expects the columnNumber.

A very verbose way to do this could look like this:

-- takes *one* Int

-- returns a function that turns another Int into Html

fieldInRow : Int -> (Int -> Html Msg)

fieldInRow rowNumber = fieldView rowNumber -- this is partial application

rowView : Int -> Html Msg

rowView rowNumber =

let

columnNumbers = range 0 10

in

map (fieldInRow rowNumber) columnNumbers

And now comes the  moment.

If we remove the parenthesis in the definition of

moment.

If we remove the parenthesis in the definition of fieldInRow : Int -> (Int -> Html Msg) we see it is exactly the same as

the defintion of fieldView : Int -> Int -> Html Msg.

And the functionality is also exactly the same. That’s why we can just leave the whole function fieldInRow away.

rowView : Int -> Html Msg

rowView rowNumber =

let

columnNumbers = range 0 10

in

map (fieldView rowNumber) columnNumbers

That’s the power and beauty of partial function application!